Does Israel’s right of self-defence justify all actions necessary to defend itself, including the current blockade of water, food, and fuel/electricity?

To assess the lawfulness of Israel’s defence, two fields of law are relevant: the jus ad bellum (better called jus contra bellum today) and international humanitarian law (the law governing armed conflict). The jus contra bellum regulates whether states may resort to force and even though problems regarding the concrete application of the law do exist (especially since Hamas is a non-state actor), there does not seem to be any dispute about the result: Israel is in fact allowed to defend itself. Two generally applicable limitations to acts in self-defence exist: the measures must be necessary and proportionate to repel the attacks. In view of the horrendous attacks committed against civilians in Israel, there is no doubt though that a military response—including far-reaching military operations against Hamas—is justifiable.

The second relevant legal field concerns the ‘the how’ of military operations. Even where the jus contra bellum allows military engagement, these acts must always adhere to the jus in bello, ie international humanitarian law as the field of law that regulates armed conflicts. The obligations of this legal field apply equally to all parties of the conflict.

One basic principle of international humanitarian law is that parties to conflicts must always distinguish between combatants and civilians. Only combatants and military installations may be targeted. Moreover, the law also prohibits attacks that are directed against the enemy military, but which disproportionately affect civilians.

In respect of the blockade against Gaza, this means that a blockade directed against the civilian population would be unlawful. It is especially unlawful, and even a war crime listed in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, to use ‘starvation as a method of warfare’ (article 8 2(b) XXV Rome Statute). With regard to Gaza, this means that a limited blockade could be lawful when it is meant to achieve a military aim against Hamas. An unlimited blockade that is disproportionately affecting the civilian population would be illegal.

Israel claims to have followed international humanitarian law in providing advanced evacuation warnings to residents in northern Gaza, thereby protecting civilian lives. However, others say this is tantamount to the forcible displacement of about one million people. Some even use the term ‘ethnic cleansing’. How can an objective assessment of this situation be made in international law?

International humanitarian law aims to prevent the displacement of the civilian population, and parties to the conflict are under an obligation to prevent displacement caused by their own acts. Ethnic cleansing—which means changing the demographic composition of a territory—is always prohibited and constitutes a clear violation of international law.

However, sometimes an evacuation can be lawful or even a demand of international humanitarian law, namely where it is necessary to protect the civilian population from the consequences of an armed conflict. Israel is exactly claiming to protect civilians by ordering their evacuation. Since Hamas is hiding among civilians and is hiding its infrastructure, it is particularly difficult to target them. Evacuating civilians from the war zone is a crucial way of protecting them. There comes a problem though: the evacuation must not itself lead to a humanitarian catastrophe, which can of course easily happen where around 1 million people have to leave their homes. An evacuation order can itself become disproportionate where it creates immense civilian suffering, for example because there is no infrastructure available where the civilians are supposed to go to.

An objective assessment is very difficult here. One reason is that the facts on the ground are difficult if not—under the current situation—impossible to establish objectively. What is it in concrete terms that Israel is targeting in the North of Gaza? How big is the military advantage? On the other hand, how immense is the civilian suffering? Time will also be a factor here, as obviously the longer the evacuation lasts, the more severe the suffering becomes.

As we are operating with quite open-ended legal concepts here and are applying them to situations of immense factual uncertainty, it is currently—in our view—difficult to arrive at a halfway objective assessment. Such an assessment requires detailed investigations on the ground, which are currently not possible in Gaza. This does not mean, however, that such assessments won’t be possible in the future. Fact finding missions—be they mandated by the United Nations or be they independent missions—can help to provide a clearer picture of the situation. Nevertheless, uncertainty will remain as the relevant legal concepts give significant leeway to the parties of the conflict.

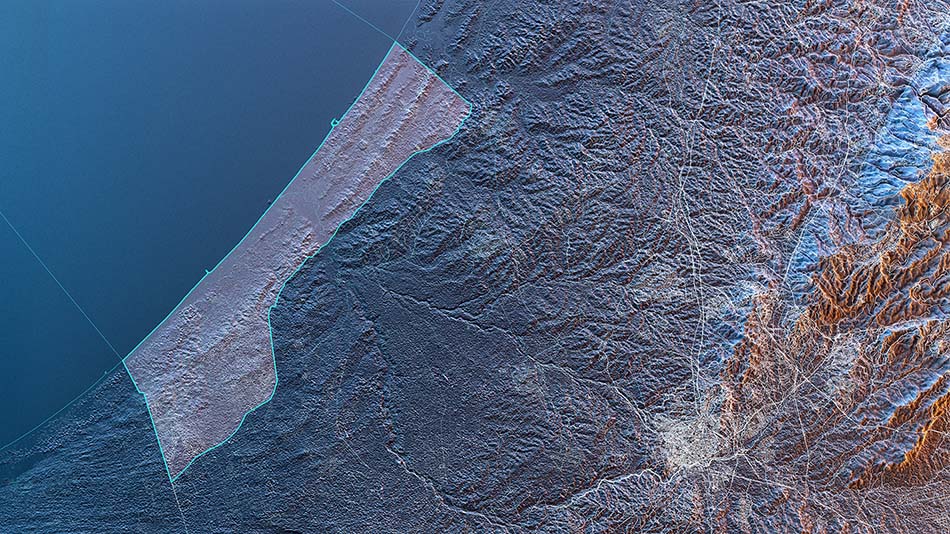

What obligations, if any, does Egypt have in international law with regard to opening the Rafah border crossing to Gazan refugees seeking safety?

Egypt is generally under no obligation under international law to open the Rafah border crossing for Gazan refugees. Both the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Egypt is a member state, do not contain obligations to admit refugees onto the territory of a member state. The Refugee Convention contains state obligations with regard to refugees that are on the territory of one of the member states. Most important in connection to the ongoing conflict is the prohibition of ‘refoulement’ (article 33), which prohibits Egypt from sending Gazan refugees back to the Gaza strip as long as the hostilities prevail. Likewise, refugees that enter Egypt illegally may not be punished for their illegal entry (article 31). However, the Refugee Convention contains no obligation to allow these refugees to enter another state in the first place.

Similarly, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights does not oblige Egypt to admit refugees from Gaza onto its territory. Although the Covenant contains a right to life, which corresponds with a state duty to ensure and protect the right to life, the Covenant only applies where a state exercises ‘jurisdiction’ (article 2). A state primarily has jurisdiction on its territory. Although there are some exceptions when states exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction, none of these exceptions apply in the situation at hand.

The 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration does contain the objective to ‘Save lives and establish coordinated international efforts on missing migrants’. However, this objective does not result in an obligation to admit migrants, whose lives are endangered. States were very careful during the negotiations leading up to the global compact not to include a ‘right to migrate’. Furthermore, the Global Compact is not binding under international law as it was adopted only as a resolution of the United Nations General Assembly.

Therefore, Egypt is under no international legal obligation to open the Rafah border crossing for refugees from Gaza.

What is the role of human rights in the current conflict?

Israel is a member state of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Therefore, Israel must respect, ensure and protect human rights on its territory and where it exercises jurisdiction. According to the International Court of Justice, this is also the case during an armed conflict. However, International Humanitarian Law—the law that governs armed conflicts—is the more specific legal regime during ongoing hostilities. Therefore, International Humanitarian Law must be considered when applying human rights law with regard to actions taken by the Israeli Defence Forces. For example, if a use of force against individuals is in compliance with International Humanitarian Law it will not be arbitrary under human rights law. Accordingly, human rights continue to play a role in armed conflict, but they will also often have to give way to the more permissive rules of International Humanitarian Law.

Palestine ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 2014. However, Hamas is not the Palestinian government but a non-state actor. Therefore, Hamas is not bound under the Covenant or other human rights treaties.

Can the solution to the conflict be found in the rules, institutions, and courts of international law, or should this ultimately be left to politicians and diplomats?

International law is central to the conflict and its resolution. First, the rules of international law govern how this conflict may be waged. The jus ad bellum determines to what extent Israel may engage in self-defence and the jus in bello sets the framework for permissible military actions. Other states, including their politicians and diplomats, have been adamant in reminding Israel to comply with these rules while exercising its right to self-defence. They have pushed Israel to enable water provisions to southern Gaza after its initial comprehensive blockade. International law is thus a central framework that guides the conflict parties and the reactions and interactions by third states.

Second, the resolution of the conflict will most likely be in the form of international law at some point, even though concrete legal arrangements are, as of yet, not in sight. Whereas the specifics of a resolution will be negotiated by diplomats and politicians, the solutions are mandated by international law. This applies both to the form of a resolution, ie a peace treaty, armistice agreement, humanitarian cease-fire or the like, as well as, to the content of such a resolution, ie a peace-keeping mission, reparation obligations, disarmament agreements, etc. Moreover, the observation of these obligations will be governed by international law. In developing a solution to the conflict, politicians and diplomats will draw on the tools that international law provides.

Third, international law will be of outstanding relevance in the aftermath of the conflict. Palestine is a member state of the International Criminal Court. The Court therefore has jurisdiction to prosecute the crimes committed by Hamas from 7 October 2023. Likewise, the Court may investigate potential international crimes committed on the territory of Palestine, including in Gaza. The International Criminal Court could therefore launch an investigation into Israeli military operations and enquire whether these violated the Rome Statute. Apart from the International Criminal Court, other bodies can be set up to adjudge the conflict, such as a truth commission, an independent expert body, or a reconciliation commission. These would also evaluate the events during the conflict from the perspective of international law and suggest mechanisms for reparation and/or transitional justice based on their evaluation.

In summary, international law is the central normative framework that regulates interactions between the conflict parties and interested third-states. Moreover, international law outlines the possible solutions to the conflict. Furthermore, international law will be the central normative benchmark in the evaluation of the conflict and will guide redemption efforts.